The history of Hebrew literature spans across the record of human civilization, with archaeological evidence dating its origins back to the 12th century BCE. When Hebrew became the state language of the State of Israel in 1948, it propelled a strengthening global movement around Hebrew literature, its ancient teachings, and progressive concepts. Today, Hebrew Book Week is observed throughout Israel each June and celebrates the religious and cultural impact Hebrew literature has had on the Jewish people.

Buried in the Soil

When beginning a journey to unlock the history of Hebrew literature, it is worth starting at its genesis. In the middle of the 19th century CE, archeological investigations began in what is now the State of Israel, with researchers surveying sites in search of evidence confirming the existence of places mentioned in the Hebrew Bible.

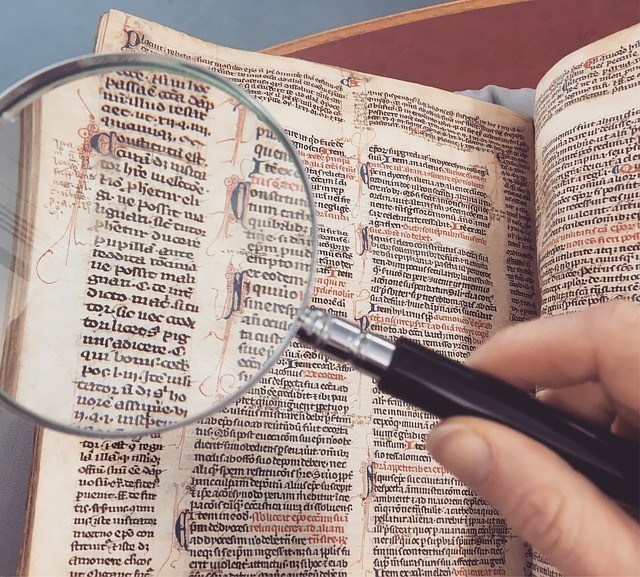

Many scholars believe that while the Dead Sea Scrolls are the oldest Hebrew manuscripts unearthed (with some dating back to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BCE), parts of the Hebrew Bible had been transcribed as early as the 8th and 7th centuries BCE. Archaeologists have yet to confirm these theories due to, in part, the perishable materials, like leather parchment and papyrus, manuscripts were copied on throughout the Iron Age (roughly, 1200 to 550 BCE).

With an estimated 20,000 recognized sites of antiquity, archaeological excavations have produced a wealth of religious and cultural artifacts as evidence of the numerous civilizations that have left an indelible mark across the literary history of the State of Israel. Those findings would serve as not only the archaeological record of Hebrew literature alone but as the findings of the history of civilization itself.

Rise and Demise

Sometime between the 12th and 5th century BCE, Hebrew literature was exclusively preserved in 20 of the 39 books belonging to the Old Testament in the form of Biblical poetry, which predated Biblical prose. Even as Biblical prose began to take shape as a literary form, elements of poetical language and structure remained.

According to Glenda Abramson, a fellow at Oxford University, the Pentateuch, consisting of the first books of the Hebrew Bible (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy) serve as the earliest recorded evidence of Biblical prose.

A large swath of ancient Hebrew literature arrived in what is now considered as the Period of the Second Temple, lasting from about 538 BCE to 70 CE. While Aramaic language predominantly replaced Hebrew as a spoken language, numerous works belonging to this period (including the Dead Sea Scrolls) showcase ancient Hebrew literature.

As Chaim Rabin, former professor of Hebrew Language at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem notes, between 500 and 1000 CE efforts of various Jewish groups attempted to impose Hebrew as the language spoken exclusively in synagogues, in place of Aramaic. Those efforts, along with others, sparked a revival that would eventually re-establish Biblical Hebrew as the literary vernacular by about 900 CE.

History of Hebrew Literature: From Rebirth to Renaissance

Spreading beyond its roots, Hebrew literary works blossomed throughout the Byzantium Empire between 800 and 1300 CE. From the historical romance Sefer Ha-Yashar (1625 CE) to the recorded travels of Jewish merchant Eldad the Danite, a renaissance in Hebrew literature developed in Sicily and southern Italy.

One of the most well-known works today that also saw a resurgence in popularity during this period was Josippon, a revision of Antiquities of the Jews written by the first-century Romano-Jewish author Flavius Josephus. This revision has remained a seminal historical record of Jewish history. Its main topic was the first century CE and the First Jewish-Roman War (66 to 70 CE). The work has been translated many times into different languages.

In both Western and Central Europe during the Crusades (between 1095 and 1291 CE) a mass migration of Jews fled to Eastern Europe. Jews who fled to what is today Germany brought with them the Yiddish they spoke and transcribed their thoughts in a liturgical poetical prose-style. This served also as a historical account of persecutions. Literary collections like Ayn Shoyn Mayse Bukh (1602 CE) and the Sefer Hasidim (1538 CE) gave rise to works centered on poetry and mysticism.

In Western Europe, particularly in Moorish-controlled Spain, Hebrew literature began to flourish, specifically in Córdoba, beginning in 900 CE. Led by Jewish scholar Hasdai ibn Shaprut and Spanish-Jewish philologist Menahem ben Saruq, Hebrew letters and idiolect saw a marked rebirth.

Samuel ha-Nagid, vizier of Grenada, gathered eminent Jewish writers of the time (including, Ibn Gabirol and Moses ibn Ezra) in an effort to promote and lend authority to the creative sensibilities of Hebrew literature. The last notable poet in Spain during this time is believed to be Judah ben Solomon Harizi, a rabbi and poet, who is credited as translating philosophical works into Hebrew.

Hebrew literature was not only featured in the prose and poetical works of the Hebrew Bible. While not as common, philosophers like Isaac Israeli ben Solomon and mathematicians like Abraham bar Hiyya ha-Nasi offered contributions to math, science, astronomy, and philosophy, all written in Hebrew.

The European Effect

Beginning in 1148, Jews began to be expelled from Muslim Spain. Many refugees fled to the French regions of Languedoc and Provence. There they translated biblical, historical, scientific, and philosophical works.

In the year 1200, a Hebrew translation of Moses ben Maimon’s Moreh Nevukhim saw a return to mysticism in the form of the Kabbala, which is a religious philosophy that promotes an insight into “divine nature.”

The apex of this movement came with the works of Spanish rabbi and kabbalist Moses de Léon’s Zohar, written in 1560. As in Muslim Spain, however, Jews were again expelled from parts of Western Europe, including England (1290) and France (1360), but mystical teachings remained popular in Italy with the works of the Italian Jewish rabbi and philosopher Moshe Chaim Luzzatto’s poetry and plays.

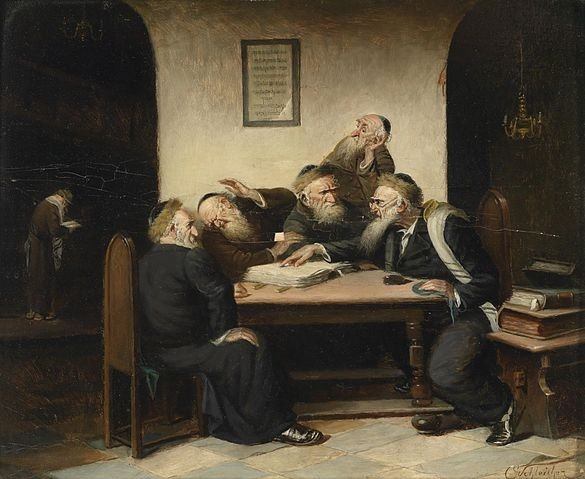

With their expulsion in Western Europe, German Jews found refuge in the kingdom of Poland. In the 15th century CE, Poland’s territory extended from what is today Lithuania to the Black Sea, and Jewish émigrés prospered and were even allowed considerable autonomy. This created an almost entirely new Jewish culture with the Babylonian Talmud replacing the Hebrew Bible as the source of intellectual thought, written in a homogenization of Hebrew and Aramaic languages.

The Jews did not escape persecution in Poland, continuing a bloody cycle of violence with the Cossack massacres of 1648. Those events were chronicled by Bohemian rabbi and Talmudist, Yom-Tov Lipmann Heller, and led to the creation of Hasidism by Baʿal Shem Ṭov (née Israel ben Eliezer). His oral teachings are noted for their use of conversational Hebrew and credited with the beginning of the literary genre known as Hebrew short story. That influence continues to dominate modern-day authors of Hebrew literature.

Intellectuals and Romantics

With the efforts of Talmudist Elijah ben Solomon, in the 18th century, a conservative mystical movement of Hasidism migrated rapidly throughout Eastern Europe and into Lithuania. ben Solomon and Orthodox rabbi Shneur Zalman of Liad were instrumental in advocating for a refinement of Talmudic training and Habad Hasidism.

Credit can be also given to Frederick the Great, who ruled the Kingdom of Prussia from 1740 to 1786, for welcoming academics and artists of the Jewish Enlightenment (known as Haskalah) into his court. Scholars like philosopher Moses Mendelssohn, Danish Hebraist Naphtali Herz Wessely, the Italian-Jewish poet Samuel Aaron Romanelli were influential on young intellectuals during this time.

The Haskalah celebrated Hebrew and western medieval Jewish literature and thrived in Austrian Poland with the Edict of Toleration by Joseph II, Holy Roman Emperor, which was declared in 1781.

As a result of this edict, the rise of satire in Hebrew literature began with works by Ashkenazi Jewish writer Joseph Perl, German Humanist Crotus Rubianus, Polish-Jewish satirist Isaac Erter, Austrian Jewish poet Max Letteris, and Austrian author Nahman Isaac Fischman.

The rise of Romanticism in Hebrew literature also found roots with the Jüdische Wissenschaft, a 19th-century school featuring critical thought interpreting Jewish literature, culture, and historical research.

In the Russian Empire, beginning around 1820, there was a budding rise against the Czarist empire, which favored orthodox over secular literature. This rise coincided with Romanticist writers of Hebrew literature like A.D. Lebensohn. Lebensohn’s notable love songs written and performed in Hebrew and the literary contributions of his son Micha Judah in poetry and biblical romances propelled a movement toward a more aggressive and socialist version of Haskalah featured in the works of critics like Nikolay Chernyshevsky and Dmitry Pisarev.

As the seeds of revolution took shape that would eventually transform Russia in the 20th century, the works of poet Judah Leib Gordon sowed the seeds in a series of ballads revealing the injustices Jews faced within the Russian Empire and would serve as a cornerstone of the foundation that created the Soviet Union.

The Modern Age

With the ascent of the middle class in Eastern Europe, their tastes and sensibilities began to dominate the themes featured in Hebrew literature. In tandem, there was a widespread movement for spoken Hebrew, and an expansion of the circle meant for readers of Hebrew literature.

Shalom Jacob Abramowitsch, best known as Mendele Mokher Sefarim, is regarded as a significant figure in the development of modern Hebrew writing in literature. After the publication of his first novel, he concluded that Biblical Hebrew did not capture the conversational tone and slang in modern subjects adequately enough and turned to Yiddish instead.

His transition successfully conveyed to readers contemporary life as it was. The popularity of his works depicting “ghetto life” would remain seminal and a characteristic style of Hebrew literature until the past century.

Memories of the Holocaust and the Literature of the New Wave

In the wake of the Holocaust, World War II and the Arab-Israeli War of 1948-1949, Hebrew was a predominant feature in Hebrew literature, as authors and poets wrote about the horrors and atrocities that befell their generation.

When the State of Israel was created in 1948, Hebrew became the nation’s official language. As a result, Hebrew literature found a permanent home and expanded upon a large scale throughout contemporary Western Europe and North America.

With rich narratives and culturally diverse themes, fiction and poetry thrived. Both Uri Zvi Greenberg’s 1951 Rehovot HaNahar and Aaron Zeitlin’s 1957 Bein ha-Esh ve-ha-Yesha both explored themes of humiliation, persecution, and redemption.

Memories of the Holocaust also haunt many post-World War II authors and their works. Works such as Aharon Appelfeld’s 1939 Badenheim, which ominously foreshadows the approaching genocide from the point of view of German Jews in sojourn at an Austrian resort. Similar themes of survival and spiritual collapse are explored in his subsequent novels, 1978’s The Age of Wonders (Tor ha-peli ʾot), 1988’s The Immortal Bartfuss (Bartfus ben ha-almavet), and 1989’s Katerina (Katerinah).

Beginning in the 1950’s up until the late 1960’s, in what is known as The New Wave in Hebrew Literature, gave rise to Hebrew literary works chronicling the socioeconomic and political struggles of immigrants, as told in Shimon Ballas’s 1946 novel The Transit Camp (Ha-Maʾabarah). Various New Wave writers, however, distanced themselves away from the realities of life in Israel and focused instead on themes of isolation, family relationships, love, and loss.

From Antiquity to Today

As a new millennium dawned, authors of Hebrew literature in the 1970’s discovered innovative ideas and styles with a heavy influence from American popular culture. Previously controversial topics like homosexuality, had begun to be addressed by some authors. The works of poets like Itamar Yaʿoz-Ḳesṭ, Admiel Kosman, Benyamin Shvili, and Chava Pinchas-Cohen explored a more metaphysical expression of emotion.

1989’s The Legend of the Sad Lakes, by scholar Itamar Levi approaches the subject of the Holocaust in a surrealistic style. Writers like Hanna Bat Shahar have explored the lives of women who are bound to the spiritual world and religious principles of Orthodox communities.

Beginning with ancient empires of long ago, to the Renaissance and Enlightenment, and into our modern world, the history of Hebrew literature is a chronicle of not only the history of the Jewish people but of human civilization. From persecution and exodus to revolution and rebirth, Hebrew literature is the record of our world.