In his book, Darwin’s Dangerous Idea, Daniel Dennett maintains that the Copernican Revolution has become an intellectual accessory of every child today, and expresses his hope that in the future Darwin’s conception will share the same condition. The Copernican theory – especially in the context of Galileo’s scientific approach – was as threatening for the Catholic Church as Darwin’s theory of the descent of man from ape. A testimony to this threat is the fact that Galileo was condemned by the Church when he explained the motion of the Earth starting from the theory of Copernicus. According to this theory, Earth was not located in the center of the universe, but was only a planet that rotated around the Sun. The theory of Copernicus is nowadays accepted without any opposition. Although the majority of Western culture nowadays also accepts the ideas of Darwin and the theory of natural selection that he elaborated, there are still voices that deny the truth of Darwin’s discoveries.

On the other hand, in the twentieth century, Darwin’s theory was complemented with the theory of DNA-based reproduction and evolution, Darwin being not yet able to explain how diversity emerges and is sustained.

Darwin and His Intellectual Tradition

After enumerating the four types of Aristotelian causes – the material cause, the formal cause, the efficient cause and the final cause – Dennett shows that in our daily life we mostly ask for final causes. He shows that there is a sort of ladder leading us from the immediate end of a thing to the universal end of the cosmos and in general of the whole of creation. Because this end is impenetrable for us, being hidden in God’s mind, theologians from the most ancient times tried to avoid this question by building a cosmogony, i.e., a story about the way in which the universe was built up.

To show the originality of Darwin’s view, Dennett presents two philosophical theories concerning the origin of order in the world. These theories belonged to the intellectual tradition, which, influencing Darwin in a certain measure, was nevertheless overcome by him.

The first conception was elaborated by John Locke. This English philosopher considered that in the beginning was the Mind, i.e., God’s Mind. He concluded this after claiming that every reasonable person would concede that matter cannot move by itself and motion cannot appear by itself, and finally that, given the existence of motion and matter, neither of them individually, nor both together, could produce thought. This is why, he concludes, that if there is thought, this thought must exist prior to matter and motion, and this pure thought would belong to God.

Another British philosopher who contributed to the philosophical tradition from which Darwin’s conception emerged, was David Hume. In his Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion (1779) he took a different path towards affirming the preeminence of the cosmic mind. In this work, the debate regards natural religion, which in the eighteenth century endeavored to support religious feeling with the means of science, unlike revealed religion which based religion in revelation.

Hume’s procedure is based on the famous traditional argument from design, that says that the perfection of the universe shows the existence of a design, which in consequence allows us to infer the existence of a cosmic designer. Although one of the characters of the dialogue shows that this design has many errors which can be remedied only with great difficulty and during a process which can last for a very long time (which would suggest that the designer is not so rational as it seemed, or possibly that there is no designer at all), the final conclusion is the same as in Locke, that there is a cosmic mind that puts everything together in the most adequate way.

Dennett suggests that Hume did not have any answer to the question of how the existence of a harmonious universe can be matched with the fact that in many places instead of harmony there is chaos.

The representation of an evolution advancing from chaos to an ordered universe was formulated not only in Hume’s dialogue, but also in the writings of the French philosopher Diderot, and in the works of the German philosophers Kant, Goethe, Schelling and Hegel. In fact, such an evolution had been described in many myths previously. Modern theories, like those of the philosophers just mentioned, had a speculative character. Dennett attributes to Darwin the merit of describing scientifically the evolution from a less developed stage to a higher stage of evolution.

Properties and Species

Darwin was born in an intellectual tradition that divided all properties of existing things into essential properties and accidental properties. The essential properties are those that make up the thing, and without which the thing ceases to be what it is. For example, thinking is a necessary feature of the human being, and we cannot imagine any human that would have no thinking and still behave like a human being. On the other hand, the accidental features can disappear, their absence leading to no change in the nature of that thing. Thus, if we cut someone’s hair, we do not affect his nature.

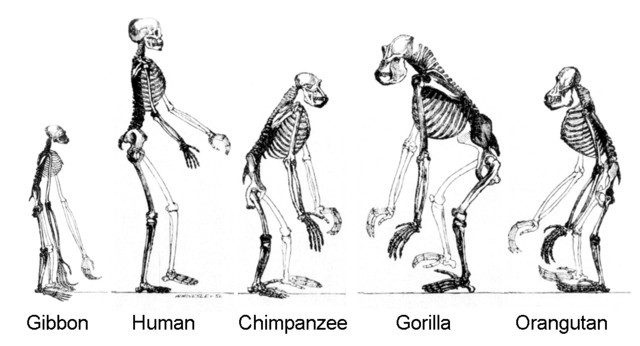

Dennett shows that the intellectual European tradition was built upon this logical pair of essence-accident, the essences remaining immutable beyond the concrete world and only the individuals changing. However, already before Darwin, many puzzling facts had been discovered about living beings, which could not easily be classified into a single group (as the idea of an essence suggests), and which seemed to belong simultaneously to different biological classes. What was more, geological findings showed that ancient relics of organisms could be similar to existing species and nevertheless different.

The Idea of Natural Selection

Besides the previously mentioned distinction between essence and accident, Darwin also inherited another idea from the intellectual atmosphere of his time: natural selection. This idea had been elaborated for the first time by Thomas Malthus in his work Essay on the Principles of Population (1798). Malthus shows here that when a population reproduces in a limited area, after a while some descendants will remain without offspring. In this way, only the better-fitted individuals of that population will be able to constantly reproduce themselves, whereas many others will disappear without descendants.

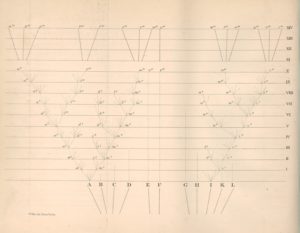

Darwin added two logical consequences to the idea of Malthus. First, that if a descendant had an advantage over others, this advantage would help it to thrive and survive. The other consequence was that this advantage tends to increase with every new generation. Darwin could thus formulate his ‘dangerous idea,’ of evolution through natural selection. According to this idea, in the course of natural changes, only those offspring will survive and thrive that are better endowed with biological qualities that allow them a better relation with the environment.

Thus, according to Dennett, it was not the idea of evolution that was Darwin’s original idea – we saw that his contemporaries had already accepted this – but that during this evolution small transformations – variations – of the organisms take place that either favor or handicap these organisms, so that, in time, those that are favored will adapt to the environmental changes.

Thus, Darwin demonstrated a logical mechanism of evolution based only on the relationship between the environment and organisms, in which God’s intervention was no longer needed. Dennett calls this mechanism an algorithm, i.e., a procedure that repeats identically during an extended period. He reminds us that we must distinguish between the idea of such an algorithm – that coordinates biological evolution – and the idea that this algorithm would have led necessarily to the appearance of Homo Sapiens. Although it is true that evolution happens through an algorithm, it is not true that the algorithm is conducive to the appearance of Homo Sapiens.

Dennett states that this algorithmic explanation of biological evolution was later extrapolated into almost all sciences, into geology as well as psychology. Everywhere the idea of small transformations adding up to a big change – a change that was no longer reducible to previous structures and which in biology is called speciation, namely the appearance of a species that is autonomous with respect to other species – got footholds after Darwin. Thus, this idea transformed the practice of scientific research.

Functions and the Modern Paradigm of Thinking

Dennett considers that Darwin’s idea revolutionized our general world-view. However, we must remember that Darwin belongs to a new paradigm concerning the understanding of the world, a paradigm that originated in a distant past, in the time of the great medieval polemic between realism and nominalism. In this polemic, the point in debate was whether our concepts of genera and species corresponded to real entities or whether they were only mental instruments and names by which we identify and distinguish things.

The nominalists won the battle, and nominalism has imposed itself slowly as the modern paradigm. In this process, our knowledge ceased to be interpreted as correspondence to the essences of things, and started to be interpreted as having its own dynamics. This dynamics anticipated Darwin’s idea. The modern representation that reality is a system – thought of at the beginning as an organism, whose structure means that all the pieces are necessarily interrelated and connected, so that if one element changes it incurs the transformation of the whole – made it already possible to conceive of existing things as results of a steady evolution that is coordinated by function-like laws. In the modern, functionalist way of thinking, relations are prior to substances and essences, in fact to real things. And Darwin is seeing organisms too as being dependent on their relationship to the environment and not being made up starting from an immutable essence.

One of the aspects of the argument from design is that natural teleology could not be understood as purely natural. Teleology implied, according to ancient and medieval thinkers, the presence of an intention, i.e., of some sort of rational purpose. Through functional thinking, the problem of teleology seems to be solved. In functional thinking, the pieces of the puzzle are no longer independent: rather they are interconnected.

For example, for this thinking, a word is not something isolated, but something that belongs to a language that makes the word possible through linguistic laws. When Darwin maintains that organisms adapt to their environment and the most fitted win in the struggle to survive, he supposes that organisms are dependent on their environment: by doing this he already creates a logical unity between organism and its environment. The population living in an environment is ruled by the latter’s conditions. The organism is no longer seen as something independent, but as conditioned by its environment. If, in the past, this conditioning was interpreted as teleology, in the new Darwinian interpretation, it results from the causality exerted by the environment upon the organism.

However, it is not only the existing environment that acts upon organisms: the size of population is also a determining factor, as well as the influence of this population on the same environment, resulting in its change. Thus, environments are not immutable either. In fact, both environment and organisms change together, being mutually dependent. They adapt to each other, environments being, of course, less dependent on organisms, in principle.

A function is rule that ensures that only those characteristics are selected which correspond to it. In the same vein, in biology only those variations will be selected that match the environment. Of course, by applying the functionalist perspective in biology, we must start in the middle of life’s evolution, as Dennett states about Darwin’s method. This means that Darwin did not start with explaining how the first form of life appeared, but somewhere in the middle of the life’s evolution, presupposing therefore an always-existing background of organisms that are changing according to the transformation of the environment.

Therefore, the new variations are only small recalibrations of existing structures of organisms. Adaptation doesn’t happen as if a newborn organism, which had never lived in any environment, suddenly adapted to a given environment. Adaptation involves existing organisms and existing environments and their mutual change. In this way, organisms are not created ex nihilo to match an environment. Through small steps, these organisms constantly transform, and from these small transformations, only those are maintained that match the environment. Dennett calls this process the principle of the accumulation of design.

Teleology and Adaptation

If we think of the organism as a system in which each part is tightly related to the whole and where a modification of one part entails the modification or the annihilation of the whole, then we can imagine the small variations as changes that either lead to a better adaptation of the organism to the environment, or, on the contrary, to its disappearance. The old teleology took organisms as immutable substances, which were given once and for all times.

People observed how well a species is adapted to its environment and they concluded that a divine mind must have created the organisms in such a way that they can survive and thrive in their environment. Think of polar bears and their thick fur: at first sight, you could say that the fur is necessary to survive in those difficult conditions and that only a divine mind could have thought of a means to solve this problem.

In this example, both the polar bear and the environment are taken as given realities, both existing independently. On the contrary, functional thinking would neither consider the polar bear in isolation from the environment nor see it as a life form which would own all its attributes independently of its environment (even seen logically). This thinking – because it doesn’t start its research from the hypothesis of a substance or essence that would rule the whole of the species, but from the idea that every existing species is only a variation of another existing species that had managed to get a sort of reproductive isolation – can see the change as a small-sized re-structuring of the organism. And this small change, although it can seem only local, is not independent of the whole organism, i.e., it involves some (maybe undetectable) transformation of the whole organism (an idea that Darwin formulates in his book On the Origin of Species)

What is more, these changes cannot be considered as intended, because many unsuccessful transformations are documented as well. If there was a single transformation, successful from the first attempt, then we could accept the hypothesis of the existence of an intention behind the phenomenon of the transformation. However, since many unsuccessful transformations are also well-documented the only hypothesis that can be accepted is that nature proceeds through trials and errors, without any previous design. The successfully emerging life-structure is thus a product of chance like any other aborted structure.

This new way of thinking was considered unacceptable by some of Darwin’s contemporaries, precisely because it reduced teleology to non-teleology, showing that what seemed a perfect fitting of organisms to their environment was only the result of very long-lasting processes of small changes within organisms in the direction of a better adaptation to their environment.

Changes and the Paradox of Motion

However well Darwin’s theory replaces the old teleology, it could not eliminate a certain aspect: the fact that organisms constantly experience small changes apparently without any cause. Darwin’s theory, then, can function only if two initial premises are accepted. These are: a) in each moment of time, there always exist a multitude of organisms having already a definite shape and structure and b) these organisms do not stay in the same form forever but run through small changes with each new generation, so that in a very extended period a new species can occur from a set of existing organisms.

It happens thus with this theory as with the ancient atomism in which everything can be deduced from atoms except their initial motion. In the same way, the fact of the small changes is a necessary prerequisite for this theory. Darwin could not yet explain from where these minor variations derive. Or, we could compare this idea with the constant of light in Einstein’s theory of relativity: here too, the speed of light is taken as being constant without any further explanation, it functions as a principle that allows the rest of the theory to be erected.

Properties and Human Knowledge

However well-established Darwin’s dangerous idea is in the scientific establishment, and however much Dennett insists on the fact that Darwin managed to eliminate the divine mind from the script of evolution, there is a point that cannot be avoided and which leaves the door open to the presupposition of the divine Mind: the idea of properties. In order to have evolution, and, what is more, to have a world in general, the existing elements must have properties and be able to enter new combinations, manifesting thus in time also new properties.

These properties cannot be explained by anything material. However complex or simple an existing organism is, its actual or potential properties cannot be explained causally. For example, we can say that things fall because they are attracted by Earth’s gravitational force. Nevertheless, the properties of being able to be attracted or to attract are ultimate facts that cannot be reduced to other mechanisms.

The capacity of sight is based on biological tissues and organs. However, all the properties of those tissues and organs that combine together making sight possible cannot be explained, but only postulated. Another eloquent example is speaking: indeed a complex brain makes the capacity of speech more probable, but only in hindsight. Only because we see speech associated with human complex brains do we deduce that this complexity is responsible for the appearance of speech. Only in that type of brain, associated with a certain type of biological structure of the entire body, does the property of being able to speak occur. However, this is only an association that we make, and not an explanation, because the properties and reactions are not further analyzable.

Metaphysics and the Ways of Being

In traditional metaphysics, there was a collection of concepts considered to correspond to some irreducible features of reality. Concepts of this sort were: substance, location in space and time, causality and of course property.

These concepts highlighted traits of reality that make up the warp with which reality is woven. It seems that although science has advanced greatly in knowing reality, this scaffolding has kept its function. In the case of Darwin’s natural selection, each variation manifests unique properties that occur and can only occur within its own way of organizing biological matter. These properties allow specific organisms to adapt – more or less successfully – to their environment.

When we consider them apart from their utility, these properties are just ‘ways of being.’ The particular way of reacting to something (which is actually what we call a property) is the specific way of being of that thing, and we cannot explain why it reacts in that manner and not in another. We only notice this way of reacting and suppose that it has to do with the particular organization of that thing. Then we associate the property of the thing with its structure and name this association knowledge.

This is a why-knowledge, whereas to ascertain the existence of properties is a what-knowledge. Since the decline of metaphysics in the nineteenth century, the what-knowledge has been more and more ignored, the entire focus of knowledge shifting onto why-knowledge.