Torah is commonly translated as “law” and is the Hebrew name for the Greek Pentateuch. Both names refer to the Old Testament books Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. However, it turns out that “law” as the meaning of Torah in Hebrew might not be the only, or even the best, translation; furthermore, the word Torah can also refer to the entire body of Hebrew religious texts and ideas—including commentaries, debates, interpretations, and lifestyle.

The Meaning of Torah in Hebrew: translation issues

Often Torah is translated to “law.” This is not entirely wrong, but other translations are potentially better. Other common renderings of the meaning of Torah in Hebrew are “guidance,” “instruction,” and “teaching.” Occasionally, it is translated to “custom,” “theory,” or “system,” as well—which, ironically, might be better translations than the more common translations. The “law” translation perpetuates the misconception that the Torah, and thus the foundation of the Hebrew faith, is nothing but a list of laws or rules. In fact, Jews would probably regard the Torah as best translated to “direction,” or even “truth.”

To confuse matters further, the meaning of Torah in Hebrew is often more than the contents of the Pentateuch: Torah could refer to the entire Tanakh (Hebrew Bible); it could also refer to the Tanakh and the Oral Torah (orally transmitted insights based on and accompanying the written Torah—now formally recorded); it can even include all of the former items, along with rabbinic/scholarly interpretations of them. On an ultimate level, Torah refers to the foundation and development of the Jewish faith through the ages.

To confuse matters further, the meaning of Torah in Hebrew is often more than the contents of the Pentateuch: Torah could refer to the entire Tanakh (Hebrew Bible); it could also refer to the Tanakh and the Oral Torah (orally transmitted insights based on and accompanying the written Torah—now formally recorded); it can even include all of the former items, along with rabbinic/scholarly interpretations of them. On an ultimate level, Torah refers to the foundation and development of the Jewish faith through the ages.

Jews sometimes refer to the Torah as Chumash, a counterpart term to Pentateuch, as it derives from the Hebrew word for five. (Penta- is a Greek originated prefix for five.) Similarly, Jewish people also sometimes call the Torah the Five Books of Moses, since Moses is the traditionally accepted author/receiver of the Torah’s contents.

The word Torah is derived from the Hebrew word for ‘cast’—as in casting seeds—or any small entity that is produced/spread in great numbers over a wide area to create a strong combined effect. Coincidentally, this is a scripturally supported metaphor for the Torah’s function in the world: The Jews (or Mosaic Covenant people, which could be interpreted to include other Abrahamic monotheistic faiths) will cover the earth, live out the truth, and spread the truth—individual to individual.

Traditional vs. Intellectual History

The traditional view, which is still held by Orthodox Jews today, is that the entire Torah, including the Oral Torah, was revealed to Moses by God; therefore, the Torah is divinely inspired—down to the letter—and Moses is its only earthly author. However, more recently, even Conservative Jews accept academic evidence that there probably were multiple authors over time who contributed to the Torah we read today.

Scholars identify four general categories of Torah authors: Jahwist and Elohist authors are distinguished mainly by their use of different names for God—Jahweh (or Yahweh) and Elohim. The Priestly and Deuteronomist sources are distinguished by their consistent writing style, emphases, and statements that at times clash with those of other Torah authors. These sources operated from around 700 BC to 400 BC—long after Moses’ time (around 1400 BC).

There are a number of theories about the order and manner in which the Torah was compiled: The most prominent is the documentary hypothesis, which suggests that a compiler/editor (or group of such people) took texts from the Jahwist, Elohist, Priestly, and Deuteronomist sources and put them together into a comprehensive whole to the best of their ability. Other theories, such as the supplementary hypothesis, differ in the order of edition/addition to the finished Torah, but generally agree about the categories of authors involved. There is considerable scholarly debate about the timing, identity, and motivation of both the editor/compilers and authors, and how to identify their contributions to the text.

While the evidence of multiple authors introduces many theological and philosophical issues, most Jews have not let this tear down their faith; in fact, many use it as a point of growth, instead, embracing the concept of an “endless Torah”—a sense of Torah that is fluid and can change with the times.

The Contents of the Torah

For another look at the meaning of Torah in Hebrew, consider the Hebrew titles for the books of the Torah. The Pentateuch titles that Christians know are actually derived from Greek and are summarizations; Hebrew titles, in contrast, are incipits—that is, the first few words of each book:

In Hebrew, Genesis is Bereshit or “In the beginning.” God (Elohim or Yahweh) sets up the earth, the entire universe, and humanity. There is the famous story of Adam and Eve and their unfortunate choice that introduced sin. God attempted to correct the fallen world by flooding out all but Noah and his family. Then, God established a holy covenant with Abraham settled in Canaan—a land God promised to him and his descendants, if they remained in connection with Him. Unfortunately, over time, sin and failure overtook the Covenant people, and they were enslaved by the Egyptians. God chose Moses as the leader to bring the Hebrews back to the Covenant land and lifestyle.

Exodus is Shemot or “names.” While Exodus (“migration” or “emigration”) might seem to be the more accurate title for this narrative, “names” gets more to the point from a Jewish perspective: Exodus not only names many people and places, it also names such important components of Judaism—the Tabernacle, the Arc, the 10 Commandments—as well as basic practices of the faith and lifestyle.

Leviticus is Vaykra or “And He called.” Again, Leviticus (“laws”) is a suitable name, since rules for proper sacrifice, including Kashrut (Kosher laws), and use of the Tabernacle—a precursor to the Temple—are enumerated. However, the Hebrew title emphasizes that God gave these laws as part of an ultimate calling that transcends mere law.

Numbers is Bamidbar or “In the desert of.” There is a bleakness to this book—numbers of the Exodus Jews fall away spiritually and perish in the desert, without entering the Promised Land. Nevertheless, a new generation is born and they remember the laws, and so the Abrahamic Covenant remains in place.

Deuteronomy is Devarim or “Items.” The Greek-derived Deuteronomy means “second law.” Indeed, both titles are appropriate, as this book of the Torah recapitulates events that occurred, as well as laws and insights God gave the people to guide them into their new life in the Promised Land. This book includes the Shema Yisrael, the definitive prayer of the Jewish faith. (Later, Jesus builds upon the Shema Yisrael in the New Testament to give his ultimate commandment for his disciples to love one another.)

In some instances, the meaning of Torah in Hebrew is the entire Tanakh, which encompasses the Torah, as well as the Nevi’im (prophetic writings) and the Ketuvim (writings of traditional Jewish history, wisdom, and poetry).

In addition, this broader meaning of Torah in Hebrew can encompass the Oral Torah, as well as rabbinic commentary texts. Originally, the Oral Torah was what it sounds like—purely oral, passed verbally and traditionally. However, after the disruptions to the faith caused by takeovers and exiles from the mid-1st millennium BC to the 1st century AD, the Jewish authorities determined that written texts were needed to maintain the integrity of Judaism. The first Oral Torah writing by Jewish scholars was the Mishna, soon followed by the Baraitot, Tosefta, Midrashim, and Gemara. However, only the Mishna and Gemara comprise the Talmud—the final, universally recognized Oral Torah.

The Torah’s Role in Jewish Practice

The Torah’s Role in Jewish Practice

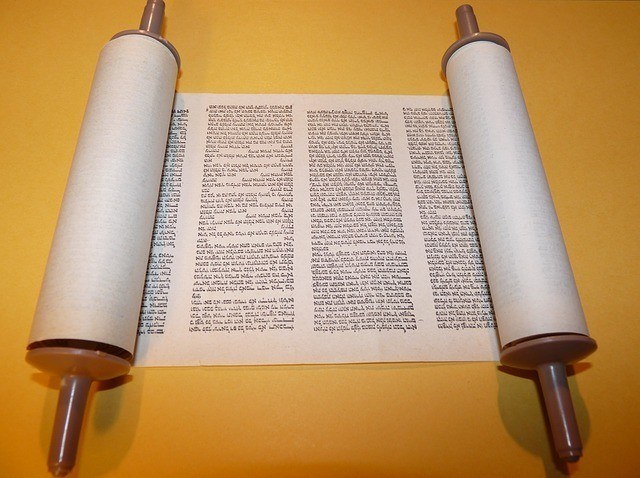

Since the Torah is the foundational text of the Jewish faith, a passage of it, called a parasha, is read at each weekly Shabbat (Sabbath) service. There are 54 total parashot chosen so as to allow a congregation to get through the entire Torah within a year. As part of the traditional procedure, the Torah is read in scroll form—known as the sefer Torah. (These scrolls are carefully produced to exacting specifications by a sofer, or expert scribe: no points, marks, or stylized letter shapes may be omitted, misprinted, or misplaced in the scroll.) The reader removes the sefer Torah from the ark (a specially crafted cabinet in the synagogue) and reads the words in a ritualized chant, also called cantillation. Special Torah passages are similarly read for Jewish holiday services, as well.

Some sects of Judaism, now mostly Orthodox Hasidic Jews, have a mystical focus on the actual letters, numbers, marks, and combinations thereof in the words of the Torah. For them, the meaning of Torah in Hebrew includes a dizzying constellation of abstract ideas about the universe and the human-divine connection.

All Jewish traditions have Torah origins—if not literally, then spiritually, symbolically, or thematically: These traditions remind the Jews of the Truth and of their special relationship with God. Some traditions arise from occasions where the Jewish people were living out Torah in different places, times, and conditions—sometimes under duress, oppression, or strong influence from cultures very different from theirs.

Philosophical Use of Torah

Historical and philosophical questions come together when debating the authenticity of the Torah. A Chabad writer argues that the Torah must be divinely inspired because there is no real incentive to deceive people about the Torah’s contents, and moreover, that it would be hard to get away with wrongly portraying information that is part of popular tradition. However, these points beg the question: What exactly is meant by such expressions as “written by other authors” or “not divinely inspired”? After all, the idea that Moses received the Torah from God is accepted as divine inspiration—Moses’ presence is not inherently regarded as a corrupting influence. Similarly, at face value, there is no reason to assume that later authors did not render the original ideas accurately.

Cultural influences and modernization have changed Jewish traditions and practices, which could seem problematic to the religion. However, it turns out that Jewish scholarship lends itself to evolution. This may come as a surprise, considering Judaism’s reputation as an ancient, tradition-based faith; there is actually a strong debate culture in Jewish academic theology.

The core of Jewish scholarly debate is the extent to which the Torah can or cannot be abrogated/reinterpreted/altered: Most scholars agree that the context and words of the Torah imply permanence and inevitability. However, we do live in a changing world: It is conceivable that what was consistent with Torah 500 years ago is not so anymore.

In some cases, apparently clashing views might just be a question of perspective. Abarim Publications suggests Torah is a description of the real world, rather than a prescription for a better existence—however, it does go on to say that the instructions are about becoming a being that better coincides with the universe’s ways. A Chabad writer seems to suggest the reverse—that Torah is about striving to make ourselves and our world true to God’s ideal. Indeed, these might not be discordant or mutually exclusive views: Both demand constructive change from human individuals.

Sociological Use of Torah and Zionism

The Torah’s emphasis on a divinely predetermined Jewish homeland lent itself to the Zionist movement. However, scholars took different approaches: Some viewed the Torah as prescribing the formation of a homeland—either as a way to free the Jews to live perfect Covenant lives as a community, or to perfect their Covenant relationship with God so as to share that perfect life and relationship with the world. In contrast, others view the striving for a Jewish homeland as a traditional component of Jewish social identity that can be discussed on a secular basis, separate from the Torah itself.

The Torah’s Relevance to Other Faiths

Most Jews would agree that the meaning of Torah in Hebrew is really ultimate truth, but it turns out that it has this meaning in almost all of the world’s major monotheistic faiths: The Old Testament is universally recognized as part of the Christian Bible. The Muslim Quran addresses the Torah with reverence and respect. Christianity and Islam—both, but in different ways—claim to uphold the Torah: Christians find textual evidence throughout the Torah that the Messiah’s salvation brings them into the Covenant community; Muslims view the Torah as true in meaning, but outdated in details and possibly distorted by human scribes over time.

The less common Rastafarian (Jamaica) and Baha’i (Middle East) monotheistic religions also draw considerable inspiration from the Torah’s laws and insights, but they theologically digress from the Torah more than Judaism, Christianity, and Islam do.

The Torah’s Universalism

The world’s most prevalent religions have origins in, and reverence for, the Torah. Moreover, many of the Torah’s core insights—prescriptions to love, respect, and help others—are universally recognizable as virtue, even to secular ethicists. The fact that its text is steeped in particulars of Jewish history obscures its potential relevance to our modern, globally connected world. Torah is not just an ancient Jewish text: It is a perennially reliable source of truth for all of us.