Book Review by Julie Porter

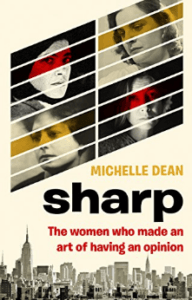

Sharp: The Women Who Made An Art of Having An Opinion

Sharp: The Women Who Made An Art of Having An Opinion

By Michelle Dean

When someone is described as sharp, it means that the person is usually intelligent, witty, and perceptive.

Journalist, Michelle Dean gathered some of the smartest, perceptive female authors who have all been described as “sharp.” Her book Sharp: The Women Who Made An Art Of Having An Opinion is a memorable look at ten women who were considered some of the best writers and thinkers of the 20th century. Dean’s writing focuses on their lives and writing to show how these women criticized the world around them, made allies and enemies with their opinions, and proved themselves to be observers and participants in shaping the world around them.

These women are:

Dorothy Parker – Literary and Theater Critic; Member of the Algonquin Round Table group of writers and performers; Poet and short story author; Known for wisecracking and witty humor like her various poems like “Resumé” which describes various means of suicide and “Big Blonde”, a short story about a depressed alcoholic and her unhappy relationships and suicide attempts.

Rebecca West – Journalist, Literary Critic, Novelist, Non-Fiction Author; Known for various works particularly Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, her experience traveling through Yugoslavia and The Return of the Soldier, the first WWI novel written by a woman.

Hannah Arendt – Essayist, Philosopher, and Political Theorist; Known for her works The Origins of Totalitarianism, a study on Communism and Nazism, The Human Condition on various political actions, and her essays on the trials of Adolf Eichmann particularly the phrase “the banality of evil.”

Mary McCarthy – Novelist, Critic, Activist; Known for The Group, about eight women from college through adulthood, The Company She Keeps, a criticism of the New York intelligentsia, and “The Man in the Brooks Brothers Shirt” a short story about a chance encounter/love affair.

Susan Sontag – Critic, Essayist, Philosopher, Political Activist; Known for “Notes on Camp”, an essay defending popular culture, and Illness as Metaphor, an essay on how diseases are described in ways that blame victims.

Pauline Kael – Film Critic for the New Yorker; Known for various film reviews, particularly I Lost It At The Movies and Kiss Kiss Bang Bang collections of her reviews, and Raising Kane, a book-length essay of Citizen Kane.

Joan Didion – Novelist, Essayist, Screenwriter, Known for Play It As It Lays, a novel about a Hollywood actress on the verge of a breakdown, Slouching Towards Bethlehem, essays about her life in California, and The White Album, a collection of various essays on different topics.

Nora Ephron – Columnist, Novelist, and Screenwriter, Known for Heartburn, a semi-autobiographical novel/screenplay about her unhappy marriage to the journalist Carl Bernstein, Imaginary Friends, a play about the rivalry between Mary McCarthy and Lillian Hellman, and When Harry Met Sally, the quintessential romantic comedy.

Renata Adler – Essayist, Film Critic, Journalist; Known for Reckless Disregard, about the lawsuits between Westmoreland vs. CBS, Gone, an expose about her time at the New Yorker, and A Year in the Dark, a collection of her film reviews.

Janet Malcolm – Journalist, Non-Fiction Author; Known for Psychoanalysis: The Impossible Profession and In The Freud Archives, criticisms of the mental health profession and The Journalist and the Murderer, which accused non-fiction author Joe McGinniss of plagiarism and violating journalism ethics with his book, Fatal Vision.

While these women were influential and inspired many women, Dean said they did not always considered themselves feminists. West was a suffragist, but she also found many of her fellow activists ferocious and prudish. Sontag wrote essays in favor of Feminism, yet she also disagreed with many prominent members of the movement particularly poet, Adrienne Rich. Ephron wrote discomfitingly about women’s organizations during the 1972 Democratic convention. The dissension between them showed many of the cracks in the women’s movement. They show that even groups that are united for a common cause such as women’s rights may not always get along. It’s human nature.

Many chapters reflect their disagreements with each other and other prominent figures. The chapter in which McCarthy bashes playwright Lillian Hellman reads almost like an intellectual catfight though the two argued politics and bigger issues than “grr, she stole my boyfriend.”

Hellman lost many allies when she lied to the House of Unamerican Activities, about her involvement in Communist groups. When McCarthy later encountered Hellman she describes her as:

“I remember that on her bare shriveled arms she had a great many bracelets, gold and silver and that they began to tremble – in her fury and surprise I assumed at being caught red-handed in a brainwashing job.”

McCarthy also described Hellman as “overpraised” in an interview on the Dick Cavett Show: “…(Hellman) is a tremendously overrated bad writer and dishonest writer… she belongs to the past, the Steinbeck past, not that I think she is a writer like Steinbeck…. I said once in some interview that everything she wrote is a lie including ‘and’ and ‘the’.” An irate Hellman then sued McCarthy, Cavett, and PBS which aired the segment. This feud inspired Ephron to write her play, Imaginary Friends.

These women also did not always get along with friends and family. West’s rocky relationship with science fiction author, H G. Wells began when she wrote a negative review about his novel Marriage in The Freewoman calling him “The Old Maid among novelists”: “Even the sex obsession that lay clotted on (his novels) like cold white sauce was merely Old Maid’s mania, the reaction towards the flesh of a mind too long absorbed in airships and colloids.”

Far from being offended, Wells invited West to dinner which she accepted. (“Somehow she was always at her most charming when disagreeing with someone.“, Dean wrote.)

After the literary equivalent of a “meet cute” Wells and West began a romance that was 50% passionate and loving and 50% argumentative and troubled.

West wrote freely about being a liberated woman and received praise for writing about topics that women were not usually known for covering at the time, like war and politics. However, her personal life was nowhere near as liberated as she projected.

Wells was married and an advocate for free love but he refused to divorce his wife or give up his other mistresses. He often gained the power in his relationship with West by withdrawing from her often leaving her to emotional breakdowns and attempted suicide.

She wrote letters that called him to task for his cruel treatment of her. However, he did not exactly hop on the clue train because he accused West of simply being overly emotional.

West and Wells continued their antagonistic relationship until 1923 when Well’s affair with an artist was the final straw. They had a son, Anthony who was also a writer and later penned a book about his troubled relationship with his mother whom he described as ambivalent towards motherhood and also concerned with her writing career which she struggled to gain back from Wells’ “constant disturbance of (her) work.” Like the other women in this book, West managed to reinvent herself by marrying well, going to America and befriending intellectuals, and writing some of her best works including The Black Lamb and The Grey Falcon.

Dean recounts many of the zingers, wit, and repartee that these women were known for. In 1957, Dorothy Parker recalled her nearly 40-year career, some of which she had been criticized for writing doggerel and shallow works (which couldn’t be further from the truth. Her works were darkly humorous and bittersweet). Parker said “As for me, I’d like to have money. And I’d like to be a good writer. These two can come together, and I hope they will, but if it’s too adorable, I’d rather have money.”

She also used her Constant Reader book reviews to cut various authors down to size such as “the affair between Margot Asquith and Margot Asquith will live as one of the prettiest love stories in all literature.”

Parker also used her witticism superpowers to speak about causes that she believed in. After the Italian anarchists, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti were arrested, many authors and intellectuals defended them including Parker.

She was arrested during a protest for the duo and pled guilty for “loitering and sauntering.” When asked if she felt guilty she responded: “Well I did saunter.”

Dean’s book shows these women didn’t just have constant rivalries, fractured families, and quick quips, but were also able to make a change with their words and writing. While Hannah Arendt was already a prominent essayist who wrote works on totalitarianism and political actions, it is her essay studying Adolf Eichmann, a member of the Nazi Party, that stands out among her works.

After WWII ended, Eichmann fled to Argentina where he was kidnapped by the Mossad and brought to Israel to face war crimes charges in 1961.

Arendt lived in Germany as the Nazis began taking power in the 1920-30’s. Many of her friends and colleagues including a former lover joined the Nazi Party.

Arendt managed to flee to New York, but she couldn’t leave the ghosts of Nazism behind. She wrote about the Eichmann trial: “I would never be able to forgive myself if I didn’t go and look at this walking disaster face to face in all of his bizarre vacuousness without the meditation of the printed word.”

Arendt’s study of Eichmann is fascinating, particularly how she coined the phrase “banality of evil:” that Eichmann like many members of the Nazi Party were average citizens who blindly let clichés and ideology think for them instead of their own sense ethics and decency. Arendt said of Eichmann: “It was essential that one take him seriously and that was very hard to do unless one sought the easier way out of the dilemma between the unspeakable horror of the deeds and the undeniable ludicrousness of the man who perpetrated them and declared him a clever calculating liar which he was not.”

Arendt’s essay “Eichmann in Jerusalem” received controversy because many critics accused her of victim blaming by calling to task the Jewish Councils in the ghettos particularly in Warsaw who assisted the Nazis by selecting Jewish residents to be shipped to the concentration camps. However, Arendt’s essay opened many eyes to the psychology of dictatorships and how they get people to follow them by seducing the people with ideology or forcing them to make terrible decisions for survival.

Sharp is a masterful book about ten amazing women who wrote works that got people talking and thinking. Above all, they always got the last word.