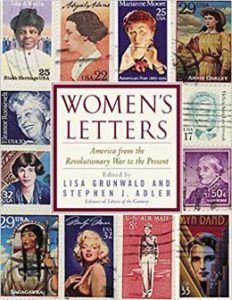

Women’s Letters: America From The Revolutionary War to The Present

Women’s Letters: America From The Revolutionary War to The Present

Edited by Stephen J. Adler and Lisa Grunwald

Reviewed by Julie Sara Porter

Primary sources are terrific means of researching history. They are first-person accounts by the people who lived them. Among the most important primary sources are letters. Stephen J. Adler and Lisa Grunwald gathered hundreds of letters by American women and girls in Women’s Letters: America From the Revolutionary War to the Present, a comprehensive brilliant book that covers the changing world from the Revolutionary War to the post-9/11, focusing not only on the relation between famous women and American history but also on less renowned women and the impact of history on their lives.

The book is arranged chronologically from 1775-2005 and recounts various letters from girls and women of various ages, ethnicities, social status, roles, and careers from medical professionals, actresses, authors, politicians, wives, mothers, daughters, and more. It is a diverse collection that tells a lot about American history and our current lives.

There are many notable figures whose letters are represented. Abigail Adams‘s correspondence with her husband John is represented including her famous “Remember the Ladies” missive dated March 31, 1776. She reminded her husband to remember the contributions that women made in organizing the Revolution against the British and told him that women should not be ignored in creating the new nation. This letter has been quoted by feminists and suffragists since.

Another First Lady who is represented in this book is Mary Todd Lincoln, wife of Abraham. She wrote to a friend on March 22, 1869, about a trip that she took with her son to Europe. At first, it seems like a normal letter, but her emotions come through as she describes her frequent illnesses and envy of the wife of then-President Ulysses S. Grant. Her letter suggests a woman who is filled with deep grief and has a tenuous grip on her sanity foreshadowing her battles with mental illness which caused her to be institutionalized.

Eleanor Roosevelt is another First Lady who is represented. Her letter is a sophisticated rejection letter to the then president general of the Daughter’s of the American Revolution, Mrs. Henry M. Robert Jr. The DAR barred African-American singer, Marian Anderson from performing in Washington DC’s Constitution Hall. Roosevelt’s letter dated February 28, 1939, reveals her decision to resign from the DAR and her unwavering support towards Anderson. Though the letter is short and succinct one could tell Roosevelt’s outrage about Anderson’s unfair treatment and her strong ability to put others in their place.

The book also recounts many of the amazing female trailblazers who were often the first in their fields. Elizabeth Blackwell, the first woman to obtain a medical license and open a medical practice in New York, has a letter. Her letter sent to an unknown recipient on November 9, 1847, described the heavy course load and the sexism from male professors and fellow students that forbade her from attending lab sessions and made her academic life a nightmare. However, her letter shows a woman of great persistence and tenacity in fulfilling her goal of becoming a doctor.

Another memorable figure is Sojourner Truth, an escaped slave turned minister and reformer. She penned a letter to Rowland Johnson, a Quaker and supporter of Abraham Lincoln on November 17, 1864. She wrote about a visit with Lincoln in which he exhibited kindness and understanding to his visitors, both black and white. In her visit, Truth was clearly pleased that she found an ally in support of her cause of emancipating slaves.

Suffragists and Feminists are featured prominently in this book. One letter reveals the breaking of ties between the National Organization for Women (NOW) founder, Betty Friedan, and author, Rita Mae Brown, after Friedan described lesbians as a “lavender menace.” In her letter from October 24, 1974, Brown challenged Friedan for her double standard towards homosexuality. She reminded her of NOW’s goals to end discrimination towards all women.

Writers are also represented, many communicating with publishers, editors, fans and other people who contribute to the publication of great works of literature. Emily Dickinson wrote to the author Thomas Wentworth Higginson on April 16, 1862, after she submitted some of her poetry to him. In a tongue in cheek letter entirely in verse, Dickinson asked Higginson if her verse “was alive” and what he thought. Many writers reading it will understand the impatience of wondering how their works are viewed and would be glad to know the great authors of the past went through the same anxieties that they did.

Entertainment stars are also featured in this book. A short note Marilyn Monroe wrote to Dr. Marcus Rabwin on April 28, 1952, offers glimpses of her anxieties. Though she was going to have her appendix removed, her note asked that he not leave visible scars and to be careful around her ovaries. Though brief, the note is telling in reflecting Monroe’s insecurities about her appearance and her desire to have children which never happened.

Not all the letters are by famous people. Many of them are from average citizens that describe the world around them. It is amusing to read these letters and realize how little things have changed in 244 years.

A perfect example is the letters Sally Wister, a Quaker teen, composed to a friend, Deborah Norris, on October 9, 1777, and June 3, 1778. While the threat of war hovered in the air, Wister’s mind was on more romantic pursuits. As her family housed soldiers, Wister was captivated by the handsome brave men in uniform. The flirtatious teenager describes an encounter with a captain that reveals adolescent infatuations never really change whether the objects of their affections are soldiers, rock singers, or film stars.

Another example of the more things change the more they stay the same is the letter Mary Dodd composed to “Frontier Widows” for the Kentucky Reporter on September 5, 1817. The letter warns women to beware of a swindler, Jesse Dougherty, who married and then abandoned Dodd but not before revealing that he already had a wife. Dodd’s no hold barred assessment of her former lover as a lying, cheating, philandering con artist is not all that dissimilar to Facebook posts criticizing one’s ex.

Some of the more fascinating epistles are the eyewitness accounts of history. Helen DuBarry wrote to her mother on April 16, 1865, of attending a specific theater performance with a very dramatic unplanned ending. She describes Abraham Lincoln’s assassination with great detail such as the popping sound, the President slumped over in his seat, and his assassin John Wilkes Booth leaping to the stage then running off. It is more gripping than reading it in a textbook.

Another gripping eyewitness account is that of the bombing of Pearl Harbor. Dorothea Taylor wrote to her brother on December 7, 1941, hours after the bombing. Taylor begins talking about the beautiful Sunday and then described the heavy black smoke rising from the direction of the Harbor. While she is matter of fact in her writing, Taylor’s panic is clearly felt as well as the idea of a seemingly peaceful moment ravaged by events beyond one’s control.