Learning Biblical Greek is a difficult undertaking, especially if you do not have prior ancient language experience. However, if you are genuinely interested, there are teaching courses that will show you how to learn Biblical Greek. A good course, like the one that we are presenting in this article, will be full of relevant applications of the language, so you will not feel that you are learning for nothing. You should find yourself motivated to keep going – even possibly to another language or cultural study.

Learning Biblical Greek is a difficult undertaking, especially if you do not have prior ancient language experience. However, if you are genuinely interested, there are teaching courses that will show you how to learn Biblical Greek. A good course, like the one that we are presenting in this article, will be full of relevant applications of the language, so you will not feel that you are learning for nothing. You should find yourself motivated to keep going – even possibly to another language or cultural study.

Greek in Historical Context

The Hellenistic Period, an age during which Greek language and culture took a powerful hold over a wide area, extended from a few centuries BC to 100 AD. Of course, the New Testament events and writings fell at the later end of this time period. However, Greek’s dominance was so great that it took it a while to wear off; one could argue that it never did.

Greek was very similar to how English is in our modern world: While there are many people around the world who do not know English, it is, on an unofficial basis, a universal language. People looking to get involved in any sort of global business or academic activity want to learn English. Greek was the same way around the Hellenistic Period.

However, ironically, English draws on Greek considerably, especially in academia. Greek’s influence is still with us: It influences our moral/ethical values, governmental structure, politics, philosophical approaches, scientific terminology, and more.

Greek in Linguistic Context

As mentioned above, Greek words became part of English; Latin also influenced English and other Western languages (called the Romance languages, from “Roman”). However, the Greek language and culture also influenced Latin language and Roman culture. So, again, Greek is still very much with us – both in words and ideas.

Greek and Latin are both inflected languages: Inflection is the use of changes to root words (or bases) to demonstrate different syntactic, and sometimes even semantic, relationships between words. Inflection of verbs is known as conjugation; inflection of other parts of speech (nouns, pronouns, adjectives, and articles) is known as declension.

Some languages, such as Chinese, are not inflected – they are called analytical languages. English is somewhere in the middle – some inflection is involved, but many word relationships are expressed analytically, with word order and helping words, rather than with changes to a root word.

Greek in the Biblical Context

You might be asking, what does Greek have to do with the Bible? After all, the Old Testament is Hebrew or Jewish in origin and the New Testament was written by people living in the Palestinian region, not Greece. However, if you look at the notes in your Bible, you see references to Greek translations. This is because all parts of the Bible have been, at some point, written in, or translated into, Greek.

Naturally, Old Testament Hebrew texts were translated into Greek during the Hellenistic Period. The most authoritative translation is the Septuagint or LXX (the Roman numerals for 70). (The significance of 70 is that, allegedly, there were 70 translators involved in creating the entire work.) The Septuagint was created between the 3rd and 2nd century BC, making it the oldest Greek translation of the Old Testament (Pentateuch/Torah, prophetic writings, and Jewish historical writings).

In this Greek-dominated world, the apostles quoted the Septuagint whenever they referenced the Old Testament. Furthermore, at that point, it made sense to write any new text (the New Testament) in Greek. Not only did most Jewish people not know Hebrew anymore, but also the New Testament was intended for anyone open to its message – Jew or Gentile: Greek was the obvious language choice.

A Great Destination to Learn Biblical Languages

A Great Destination to Learn Biblical Languages

The Israel Institute of Biblical Studies is an online learning website that has a close relationship with the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. The Israel Institute’s Department of Biblical Languages offers courses of study in Biblical Hebrew, Biblical Greek, Biblical Aramaic, Modern Hebrew, and even Yiddish.

These courses are fully accredited and give you three credits per course from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. They might even give you credit at other universities, too; however, you should check with individual universities/programs to be sure.

While the Israel Institute’s courses only take a few hours of work per week, they are designed for motivated students. A relatively large amount of information is covered in a short time, and instructors are available to lead group discussion sessions. These are high-quality online programs with higher-than-average instructor involvement.

That said, these courses offer the usual benefits of online education: the courses are recorded and so the hours are flexible, the tuition is manageable, and you can learn anywhere you get internet access. The only exception to this is that group discussions have to happen with the group, so take this into consideration as you are planning your enrollment in a course.

Biblical Greek: the Entire Curriculum

The Israel Institute of Biblical Studies’ Biblical Greek curriculum comprises 2 courses – the first one leveled at “beginner” and the second leveled at “improved.” However, this short Greek program is still extensive: both courses take about 9 months to complete and cover a considerable amount of material each week. By the end, you will be able to understand the nuances of Greek expression and understand translation choices applied to the Bible.

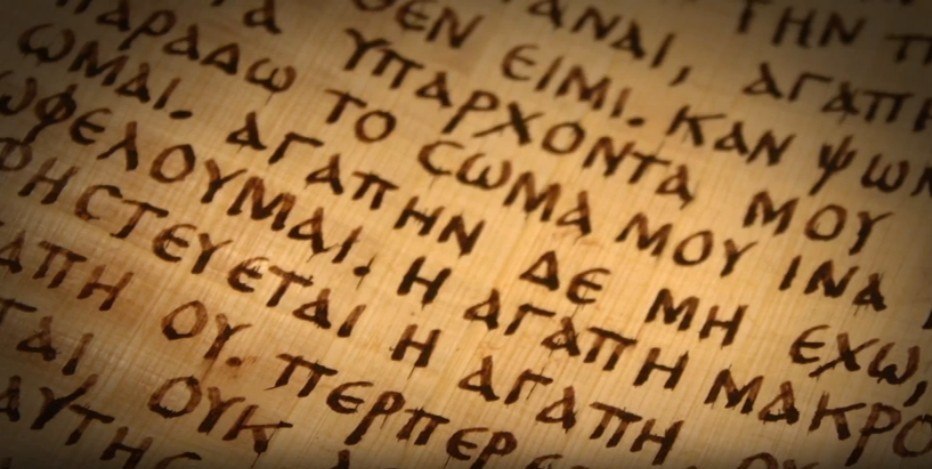

The Greek featured in these courses is Koine Greek – the Greek used in the Septuagint and New Testament. Koine Greek could be considered a “later-ancient” version of Greek that was dominant during the Hellenistic Period and the Apostolic Age. It maintained prominence during both the expansion and division of the Roman Empire – especially in the Byzantine (Eastern Roman) Empire; in fact, it still is the language of the Greek Orthodox Church.

Throughout both courses, cultural, historical, artistic, as well as biblical elements are featured, so it is easy to keep the course in context. This is a great curriculum for someone looking to gain skill in ancient Greek/ancient languages and linguistics, Jewish and/or Christian studies, theology/religious studies, and even archeology. Prominent works of Christian and Jewish art history are featured, as are prominent sites of Christian and Jewish archeology – including those from the Eastern/Byzantine tradition.

Beginning with Biblical Greek

In the beginner course, you start with the Greek alphabet – this is essential, since the Greek alphabet is different from the Arabic letters used in English and other Western languages. The Greek alphabet was developed between the 9th and 8th century BC, heavily based on the Phoenician alphabet. It finished its development in the 4th century BC, when the Euclidean Greek alphabet became the standard: This alphabet went from alpha to omega – which explains Jesus’ statement, “I am the Alpha and the Omega…” (Revelation 1.8).

Greek was the first alphabet ever to have letters representing both consonant and vowel sounds. This course compares and contrasts the Latin and Hebrew alphabets with Greek – giving the student a bit of an overview of these three ancient languages.

This course covers orthography (the study of spelling) for Greek, and it goes over various ways that Greek has been written over time: This includes uncial, or “big capital,” forms of letters, dated to the 4th and 8th centuries AD, and minuscule (or cursive) forms, used in the 9th and 10th century AD.

Basic biblical elements are featured: The names of the Pentateuch books as written in the Septuagint are covered. The trilingual sign put over Jesus’ cross is an excellent representation of the language environment of the day (Hebrew, Greek, and Latin). The Lord’s Prayer (Luke 11, “Our Father, who art in heaven…”) and the Genesis account of the seventh day (God’s rest, the Sabbath) are translated, too. John 10 (a parable of Jesus describing himself as the only true shepherd) is translated. The course also discusses the theme of the “good shepherd” and its correspondent characters/elements in Greek mythology (most prominently, Orpheus).

Finally, the course goes over the story of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10), the story of the Centurion’s slave/servant (Matthew 8, Luke 7). Accounts of healing in the Bible are featured heavily.

Of course, no beginners’ language course would be complete without grammar studies, and this course does not disappoint. It discusses diacritical (pronunciation) elements of the Greek language, including breathing marks – to indicate instances of rough breathing (with an “h” sound) and instances of soft breathing (no “h” sound).

It discusses the morphology of Greek nouns – the morphemes of Greek. Morphemes are small units of meaning in a language: morphemes are put together in intuitive ways to create words. Examples of morphemes are affixes (prefixes and suffixes), such as “un-” or “mis-” or “-ful” in English, along with the root words to which the affixes can be applied.

The course covers fundamental details of Greek syntax: For example, it turns out that, in Greek, there are substantive adjectives – adjectives that operate without nouns – much like Les Miserables (“The Miserable Ones”) in French.

The course moves on to definite article declension – this allows a definite article to agree in case, number, and gender with the noun it accompanies. Different cases exist in different languages, depending on how inflected the language is: In English, there are the possessive, subjective, and objective cases.

The course covers conjugation of common Greek verbs, declension of common Greek nouns, prepositional phrases, noun gender, word order, and the tenses – such as the present, imperfect, and future indicatives. (Imperfect implies action that was not completed at a definite time – as in, “I was walking” or “I will be walking” as opposed to “I walked” or “I will walk.”)

The course discusses, among other verb forms, the middle and deponent verbs. Deponents are verbs that are written as though passive but have an active meaning. Middle verbs are like reflexive verbs (an idea that is familiar if you have taken French) – these verbs suggest that the subject of the sentence is acting on him/her/itself.

Improving with Biblical Greek

The second course builds considerably on the first, but ultimately, it has a very similar format. Now that the student has a great vocabulary, the readings can be more substantial and meaningful: The course covers writings by Titus Flavius Josephus (the Jewish historian living in the Roman Empire) and the epistles of Paul that appear in the New Testament. With greater linguistic skill, the student is also ready to take on comparative literary studies of the Old and New Testaments – the New Testament frequently quotes, and otherwise alludes to, the Old Testament.

This second course introduces and elaborates on the Aorist tenses: In some cases, the Greek Aorist tense is comparable to the simple past tense in French – it does not specify perfectiveness – it simply indicates that a thing happens/happened/will happen, etc.

The course also elaborates on the various uses of participles (“-ing” or “-en” in English) – they can be used analytically as other forms, such as adjectives, nouns, or adverbs.\

The course discusses different moods, such as the subjunctive – a mood that expresses doubt or uncertainty, as opposed to the indicative, which is used to make statements. This is tough for English speakers, since moods are generally expressed analytically in English.

This course includes a number of meaningful Bible translations: The Transfiguration – both of Moses and of Jesus; the texts about the period from the Resurrection to the Ascension of Jesus; the Magnificat (Song of Mary) in Luke; and more cases of Jesus’ healings.

Finally, this second course goes deeper into Jewish traditions and their connections to Christian themes: the period from Resurrection to Ascension is discussed in relation to the Jewish holidays of Passover and Shavuot/Feast of Weeks (Shavuot is known as Pentecost in Greek); the texts of Jewish phylacteries/tefillin (Biblical texts worn during prayer) are discussed. The course makes a powerful finish with the 96th Psalm, which is sung on Friday night pre-Sabbath Jewish services (Kabbalat Shabbat): this text is noteworthy for its emphasis on God as creator and sustainer or all – all peoples and all of the natural world.

Biblical Greek Might Be the Best Start

If Christian and Jewish Bible studies are of interest for you – Biblical Greek is the perfect way to tie history, archeology, art, and culture to your religious studies. Biblical Greek gives you the linguistic skills to move on to Ancient Greek and Modern Greek, as well as Latin, and even the Semitic languages (Ancient and Modern Hebrew, Aramaic, and others). Greek culture defines the secular world in which Jewish and Christian influence took hold, and in that way, it is the best approach to understanding what brought us to where we are now.